Moana Love

Community Muralist

Moana Love

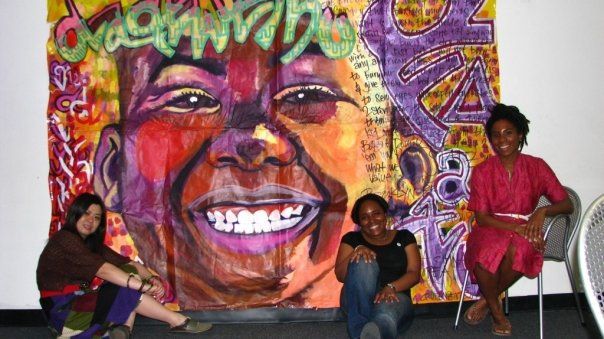

When reflecting on our interview with Moana, the word that comes to mind is “sisterhood” in its purest sense. She embraced us at first encounter and immediately an atmosphere of familiarity was set. Moana’s energy is vibrant and contagious. She is all smiles and relaxed. We instantly dive into the topic of identity, a conversation that can be trusted with care among womxn of color, as we can share the journey of finding it, protecting it, and strengthening it.

Hailing from Tonga (pronounced “TONG-UH”), Moana is fiercely proud of her indigeneity. Tonga is an island in the South Pacific with Fiji and Samoa as its neighbors. Moana asserts that Tonga is a nation with its own sovereignty filled with scholars, philosophers, artists, to just name a few of its inhabitants. It is an intellectually rich culture that the vast majority of the west fails to recognize. Moana’s indigenous roots is the foundation of her work as a community muralist. She tells us that she is “just the conduit of [a] mural” that a community commissions. As someone who understands what it’s like to have people take from her, Moana’s work is thoughtfully created with community members and it is emblematic of their resistance, pride, and ownership. This Spotlight beams, not only with Moana’s passion, but also with the vigor of the people she’s come to know.

For people who may not be familiar with tonga, what is one thing we should know about your culture?

Well first of all, to give a geographic location, Tonga is an island country in the South Pacific and it’s right next to Samoa and Fiji. What I want people to know about Tonga, even though a lot of people don’t know about Tonga, is that Tonga actually knows a lot about the world. We are hip to the world, politics, pop culture, television, etc. We know whatssup. But the world don’t know whatssup about us. I think every single country in the planet knows about the United States, so Tongans not only know about the United States, but they they know they are an invisible country to the rest of the world and despite this, we have so much pride in our culture, history, and ancestry. Being a country that was colonized by the British, Tongans are bilingual in Tongan and English. And there are many Tongans in Tonga who are like, “Yo, we are Tongan, let’s just speak Tongan.” I love that because that tells me that Tongans are still like, “Hey we exist, you may not know about us but we are gonna keep our language and our ways of life.” Tongans are definitely scholars, philosophers, artists, and historians in conjunction to what you stereotypically see us if you see us at all: football players and other athletes, entertainers, and happy go lucky people. We’re a very intellectual culture and a lot of people don’t know that because they like to pigeonhole us as “Polynesians.” I don’t even like using that word “Polynesian” because that’s not an indigenous word that we call ourselves. And that’s not a word that encapsulates who I am as a human being.

The mass media--especially with the Disney movie Moana--likes to pigeonhole “Polynesian” culture as this romantic, exotic paradise. Tonga is one of the hundreds of islands in the South Pacific that has been affected by climate change, imperialism, exploitation, and greed for so many years. Hellooo, hundreds of nuclear bombs were tested on the Marshall Islands by the United States. Most of the islands in the South Pacific are or have been Military sites. The Pacific Ocean is not only the largest body of water on the planet, but it also holds the largest waste dump on the planet. We are indigenous people who live off the land and the ocean, which means we know the Pacific Ocean and the land like the back of our hands. We have been talking about all the first-world countries’ waste and been on the receiving end of that negative impact. When people see us they’re like, when they figure out we exist, “Tongans are islanders who are just having fun on their little island.” Actually, we are (lol) and we’re not at the same time. We’ve been trying to have the world see that American capitalism and First World, power-hungry, greedy culture does not work for any of us, for the longest time. I want the world to know that there are people who exist there and have their own lives and they really have their own sovereignty. I want the world to know that we want to say something to the world and I hope that the world will listen to us.

You were born in tonga, raised in hawai'i and utah, lived in new york, and now you're living in palestine. how do you define home?

I define home as whatever you want it to be. Seriously. Because I have been in all these places, I am really sensitive to place and the context of place. I’ve been to so many places and time zones throughout my entire life and being an indigenous Tongan Oceanic womxn, we have our own definition of what place is and what time is. Place is not an exact geographical location and as indigenous Tongan Oceanic people, we define place, specifically space, as rhythm of time. So that means every space has a different rhythm and it has a different energy. And we’re energy, so how we act or how we respond in a different energy, creates that place, that specific space. Connecting that to home, for me, can be a specific object, like food, because it carries a certain energy and definitely feeling. I love lupulu that’s one of my favorite Tongan dishes--that’s home for me in certain times and places. When I get a hug from one of my best friends, who is not a biological family member, but a created family member, that definitely feels like home to me. Smelling fresh paint, that’s home to me. When I smell fresh paint, I feel my best. That’s when I’m in my element and I can create anything.

I feel like that’s my way of survival--how I define home. It’s because I understand that my family moved away from my ancestral homeland to this other place, Utah, which is supposed to be “my home,” but no, not really. I got connected to the Indigenous people of Utah. And I learned what home and homeland means to them in the face of settler colonialism and genocide. I also learned that connecting to them and feeling solidarity with Indigenous people, that inside of that, Turtle Island can be home for me. Because I can see and feel that sharing indigenous values of love, kindness, and generosity is home to me.

Activism can take many forms. is there one medium that you find most effective and what currently resonates with you the most?

It would definitely be art. The arts in general; creativity. I’m a painter, I’m a community muralist, but I’m also a performer, an actress, a writer, a poet, and songwriter with Mahina Movement. We sing and perform together in various venues. From musical spaces to classrooms and auditoriums at colleges and universities, high schools to community centers, churches, museums, galleries to the streets. The arts have really given me the ability to have my voice heard and to have me be visible because I definitely was such a shy kid, or even coming to NYC I was like, ‘please don’t look at me!’ As womxn of color, we’re always looked at in a certain way, but we’re not visible in these other ways. I want to be heard in how I want to be heard and it wasn’t until I wrote my first poem and performed it that I felt I was seen and heard fully, 100 percent. I felt gotten and visible. For me, creativity is just a direct correlation to the universe, to the source, to god--or however you define god. You’re a creator too; we all have access to being creators and so the arts is so important and so necessary. It’s just life and how life forms. It’s how people feel joy and happiness because something was created. I totally believe in the arts as activism.

murals are the pride of neighborhoods and sometimes a response to gentrification. as a painter and muralist, what makes you most excited about a new piece?

It’s really important for me to say, I am a community muralist and I do community murals. I never say I just paint murals or that I’m a muralist because it’s so important for me that people know that I work with communities and what’s on the walls belong to the community. I never sign my murals. You will never see my name on them unless the community puts it there. I never sign them because the whole part of my community mural process is that the community owns the mural and why should my name be on that? Their stories are theirs; they are not mine. I am an indigenous person and I know what it feels like to have people take things from us without even recognizing us as that creator. Everything that goes on the wall is what the community says goes on the wall. I just happen to be the conduit of that mural.

First and foremost, my murals are about building relationships. The mural that I created in Brooklyn and why I chose to do it in Sunset Park was because I was a teacher there. I was doing a theater residency and I fell in love with the kids there and their stories. My mentor, Ping Chong (Ping Chong & Company), created this really simple yet profound theatre where the community invites him to come into the community and collect stories from their community. He will collect their stories and they will read--it’s not a script, it’s not a performance--their stories in chronological order starting from when their parents met and he sticks it inside a historical context. I got to know him because he created an Asian American Pacific Islander community, “Secret Histories” as he calls it. From working with him in that show, I co-created the curriculum with Ping Chong, to take this method to young people in Elementary Schools, Middles Schools, and High Schools. When I heard their stories, I knew I not only wanted to tell their stories on stage but I wanted their stories to be respected, heard, and acknowledged in a public, community way. And that’s why I chose to do a community mural in Sunset Park. I learned about my own process by going through experiences of outreach, building relationships and really listening to peeps. In talking with the community, I asked them what they want. It took me a year to find community partners because I wanted to find the right ones. I had classes for 4 months with mothers and their children in creating art and telling their stories. We shared so much together. It’s really a lot of work and amazing fun and fulfillment. When people look at the murals and they’re like, “Wow that’s so dope!” I really would love and hope they see all the work--all the relationship creation and building. For that’s the most important thing to me about doing these community murals: is the quality of the experiences and exchange with the community and humanity. The actual mural is just a small part of the whole process. The community mural is the end visible result of all the building, creating, and experiences I have had with the community.

how much time do you spend to really understand who lives in a community and who is from the community?

Because we have so much access to demographics, to records, it really is just like 3-4 hours. It’s like, ‘let’s look up the demographics of Sunset Park and what’s this neighborhood,’ and of course I’ll spend more time on the history of the community. Sunset Park has Puerto Ricans, Arabs, and the Asian community together all in one neighborhood. So then, not only when I read the facts, the statistics of when they came to the neighborhood, who lives where, but it’s like okay, what’s in the history, or what happened during that time that they immigrated, and why did they immigrate, that will definitely take more time. But seriously, it doesn’t take that much to be like, ‘Hey, I really want to know who lives in this place and I care about people and their lives.’ I feel like that’s why gentrification happens because businesses, people don’t give a F about people.. They care about money, capital, profit, and beautification. As for me, I am an artist that wants to beautify public spaces but not in the context of capital and erasing people and history who are there and have been there.

how have the communities you've had the opportunity to share your work with responded or engaged with the work?

Every mural that I go to, I just feel so fulfilled. I remember when we were painting in the South Bronx, everyday people--strangers, kids, the elderly--would not only stop and talk to me and be like, “Thank you!,” but they would call me pintura. That means the world to me because as a young womxn of color growing up, I wanted to be a muralist, I wanted to be a painter, and when the community affirms that and calls you that, you’re just like ‘okay! This feels so good.’ The community mural in Sunset Park is called, “We Come From the Future” and it features grandmothers, their daughters, and their granddaughters. When I’m just walking in that neighborhood, people are like, “Hey, you’re the one that paints!” They will talk about how important it is to them. One of the mothers and daughters that I painted, and it’s actually the biggest portrait on the mural, is a Muslim Palestinian mother and daughter. With all of the islamophobia happening, I get so much feedback like, “You don’t even know when I see that I’m just like YES, I’m celebrated. I’m not hated!” That makes me so happy.

In Palestine, people to this day will bring me food on the street, all the kids are like “Moana, Moana!” There is not one day that I can walk in Palestine and not have someone calling out fannan. If the community wants the mural and they like it, then I know I did my job, and that can only be achieved through building a relationship with them--talking to them, hanging out with them. One of my murals in Palestine I did in two days because one of the young men got killed and I still don’t speak Arabic, so I definitely had to use other ways to show them that this is for you. Because I’ve done so many murals and they’ve experienced me making it, they trust me. The trust is so important to me and I don’t take that lightly. Once I get trust from someone, and a community, I don’t ever want to mess that up.

on ownership and consumption of art.

At a very basic level, it’s connection. That’s why storytelling is so amazing. We have been telling stories since the beginning of time because that’s how we connect and relate to each other. Now when you bring in things such as profit, that’s a whole new situation because that means one person has to be used and the other has to consume. Not that money, profit, or an exchange have to be bad or evil, but when we add that a person is being used and another person consumes, then you have to add that someone is being disrespected and the other person is respected.

When I create something, I really want people to leave feeling like they own it. Not in an ownership that is a possessive way in possessing an object. But an ownership like, hey this is my heart and I want you to have it. I give this to you. Please receive it with care.

what projects are you currently working on and how can we continue to support you?

I am going to Kenya for the first time! I’m going to Nairobi and that will be my next community mural. I am really excited about that and then I’m going back to Palestine to do more murals and theatre with children and womxn.

I am also creating a web series. I have these great friends who I consider my brothers in Tulkarem. In the U.S., we are constantly shown the only narrative of Arab men are either 2 things: they are either Terrorists or Victims of War and nothing in between. This web series will flip this narrative. My brothers are regular 20-somethings who want to live their life in their own way. I just feel like this narrative is never told to Americans and to the west. This web series is really about their everyday lives. To me, what’s so exciting is their relationship with each other. There is just so much love and tenderness between them. I thought about this after watching Moonlight. I just love Moonlight so much. I was so inspired and blown away from that movie. I just wanted to create something where the West could see and just tap into these young Palestinian men’s lives and see them navigate occupation, witness their romance and heartbreak, seeing them navigate various experiences like, ‘Man, I really want to drink alcohol, but I can’t because of my religion,’ or ‘I really want those jeans, but I don’t have money.’

How can y'all support? I just love the support of people listening to my story. How cool is that? I really wish everyone had that experience of ‘Hey, I really want to interview you and share your story.’ That’s why I love murals so much--I’m like, “I want to paint you; I want to share your story.” LOL, but I can use some monetary support if you got it to give. All my community murals are funded by me. They are all independent and grass roots. I volunteer my time, labor and skills to organize, teach, and mentor others so they can continue the community murals on their own. I also use my own money that I have saved up just so that these community murals may be created. If you can donate please send money through Venmo. My name is Moana Love and my email is indigoartista@yahoo.com on Venmo. Any amount of donation is necessary and totally received with so much gratitude.

Follow Moana on Instagram

Listen to Mahina Movement's work on SoundCloud

Follow Mahina Movement on Facebook

Photographs courtesy of Moana.